BBC News

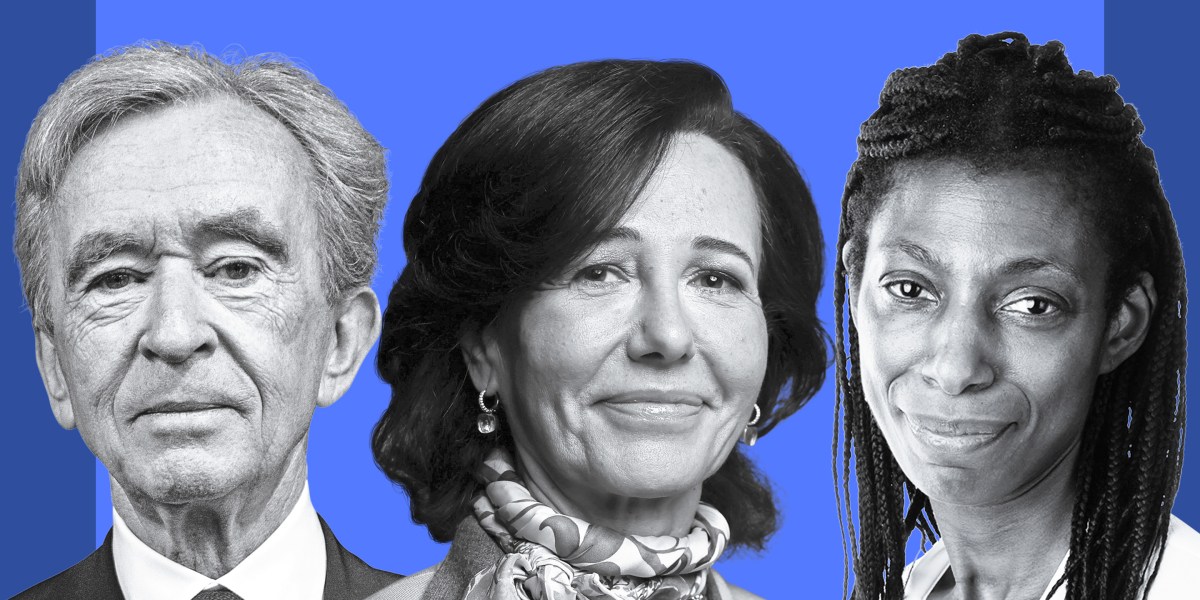

Plug entertainment

Plug entertainmentThe scenes taking place in Nigeria during the holiday periods could be in a film: emotional reunion in the airport terminals, champagne flowing like water in high -end clubs and Afrobeats Afrobeats artists overlooking the scenes to a packed audience.

It is at this point that the Nigerians abroad come back for a visit to the country of origin. They are nicknamed that I have just returned (IJGB) and brings with them more than complete suitcases.

Their Western accents plunge into and out of pidgin, their portfolios are stimulated by the exchange rate and their presence feeds the economy.

But it also highlights an uncomfortable truth.

Those who live in Nigeria, winning in the local nairas currency, feel excluded from their own cities, in particular in the economic center of Lagos and the capital, Abuja, as prices increase during festive periods.

Residents say that this is particularly the case for “Detty December”, a term used to refer celebrations around Christmas and New Years.

Detty December makes Lagos almost invited for residents – traffic is horrible, prices are swelling and businesses cease to prioritize their regular customers, a radio presenter based in Lagos, told the BBC.

The personality of the popular media asked not to be named to express what some may consider controversial opinions.

But he is not the only one to have these views and have some reflects, with Easter and the summer holiday season of the diaspora, that the IJGB helps to reject the fracture of the Nigeria class or that it makes it even wider.

“Nigeria is very classist. Ironically, we are a poor country, so it’s a bit silly,” added the radio presenter.

“The gap of wealth is massive. It is almost as if we were apart.”

It is true that although Nigeria rich in oil is one of the largest economies in Africa and the most populous country on the continent, its more than 230 million citizens are confronted with enormous challenges and limited opportunities.

At the start of the year, The oxfam charitable organization has warned The gap of wealth in Nigeria reached a “level of crisis”.

The 2023 statistics are surprising.

According to the database on global inequalities, more than 10% of the population held more than 60% of the wealth of Nigeria. For those who have a job, 10% of the population won 42% of income.

The World Bank says that the figure of those who live below the poverty line are 87 million – “the second poor population in the world after India“.

AFP

AFPMartins Ifeanacho, professor of sociology at the University of Port Harcourt, said that this gap and the resulting classes has increased since the independence of Nigeria compared to the United Kingdom in 1960.

“We have crossed so many economic difficulties,” BBC told BBC

He points to his finger on the greed of those who are in a political power position – whether at the federal or state level.

“We have a political elite that bases its calculations on how to acquire power, amazing wealth in order to capture more power.

“Ordinary people are excluded from the equation, and that is why there are many difficulties.”

But it is not only about money on the bank account.

The wealth, real or perceived, can dictate access, status and opportunity – and the presence of the diaspora can enlarge the fracture of the class.

“The Nigeria’s class system is difficult to identify. It is not only a matter of money, it is a question of perception,” explains the radio presenter.

He gives the example of going out for a meal in Lagos and how the peacock is so important.

In restaurants, those who arrive in a Range Rover are quickly taken care of, while those of Kia can be ignored, explains the radio presenter.

Social mobility is difficult when the richness of the nation remains in a small elite.

With chances stacked against those who try to climb the scale, for many Nigerians, the only realistic path to a better life is to leave.

The World Bank blames the “low job creation and entrepreneurial perspectives” which suffocate the absorption of “3.5 million Nigerians entering each year”.

“Many workers choose to emigrate in search of better opportunities,” he said.

Since the 1980s, the middle class Nigerians have looked for opportunities abroad, but in recent years, the urgency has intensified, in particular among generation Z and generation Y.

This massive exodus was nicknamed “Japa”, a Yoruba word meaning “escaping”.

Getty images

Getty imagesA survey in 2022 found that at least 70% of young Nigerians would move if they could.

But for many, leaving is not easy. The study abroad, the most common route, can cost tens of thousands of dollars, not to mention travel, accommodation and visa expenses.

“The Japa creates this ambitious culture where people now want to leave the country,” said Lulu Okwara, a 28 -year -old recruitment agent.

She went to the United Kingdom to study finances in 2021 – and is one of the IJGBS, having returned to Nigeria at least three times since her move.

Ms. Okwara notes that in Nigeria, there is a pressure to succeed. A culture where success is expected.

“It’s success or nothing,” she said to the BBC. “There is no room for failure.”

This deeply anchored feeling means that people feel that they have to do everything to succeed.

Especially for those who come from more open horizons. IJGBS have a point to prove.

“When people go there, their dream is always to come back as a hero, mainly for Christmas or other festivities,” said Professor Ifeanacho.

“You go home and mix with your people you’ve been missing for a long time.

“The type of welcome they will give you, the children who will run to you, is something you love and cherish.”

Success is chased at all costs and putting a foreign accent can help you climb the social levels of Nigeria – even if you have not gone abroad.

“People simulate the accents to have access. The more British you look, the more your social status,” said Professor Ifeanacho.

He remembers a story on a pastor who has preached every Sunday on the radio.

“When they told me that this man had not left Nigeria, I said:” No, it is not possible. “Because when you hear him speak, everything is American,” he said with disbelief.

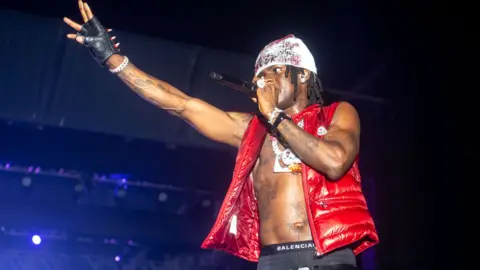

Getty images

Getty imagesAmerican and British accents, in particular, act as a different type of money, smoothing paths in professional and social circles.

The decline on social networks suggests that some IJGBS are all at the front – they can go up the addulation of return heroes, but in fact, lack financial influence.

Bizzle Osikoya, the owner of The Plug Entertainment, a company that organizes live music events in West Africa, says it has encountered problems that reflect this.

He tells the BBC how several IJGBS attended his events – but who continued to try to recover their money.

“They returned to the United States and Canada and put a dispute on their payments,” he said.

This can reflect the desperate effort to maintain a success facade in a society where each wealth display is examined.

In Nigeria, it seems, the performances are essential-and the IJGBS which are able to show themselves will certainly be able to climb the class ladder.

Getty Images / BBC

Getty Images / BBC