Scientists who recently discovered that pieces of metal on dark seabeds produce oxygen have announced plans to study the deepest parts of Earth’s oceans to understand the strange phenomenon.

Their mission could “change the way we see the possibility of life on other planets,” the researchers say.

The initial discovery baffled marine scientists. It was previously believed that oxygen could only be produced by sunlight by plants, in a process called photosynthesis.

If oxygen – a vital component of life – is produced in the dark by pieces of metal, researchers believe this process could occur on other planets, creating oxygen-rich environments where life could thrive .

Professor Andrew Sweetman, lead researcher, explained: “We are already in conversation with experts at NASA who think dark oxygen could reshape our understanding of how life could be sustained on other planets without light direct sunlight.

“We want to go out there and understand what exactly is going on.”

The initial discovery sparked a worldwide scientific row: there was criticism of the conclusions from some scientists and deep-sea mining companies who plan to harvest the precious metals contained in the nodules of the seabed.

If oxygen is produced at these extreme depths, in complete darkness, it calls into question what life could survive and thrive on the seafloor, and what impact mining activities could have on this marine life.

That means seabed mining companies and environmental organizations – some of which have said the findings prove seabed mining projects should be halted – will be closely monitoring this new investigation.

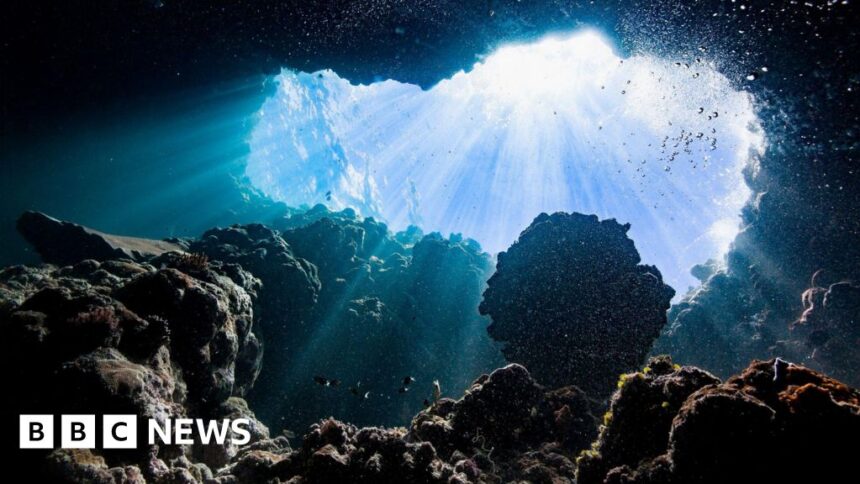

The plan is to work on sites where the seabed is more than 10 km deep, using remotely controlled submersible equipment.

“We have instruments that can go to the deepest parts of the ocean,” Professor Sweetman explained. “We are confident this will happen elsewhere, so we will start investigating the cause.”

Some of these experiments, in collaboration with NASA scientists, will aim to understand whether the same process could allow microscopic life to thrive under the oceans of other planets and moons.

“If there is oxygen,” Professor Sweetman said, “there could be microbial life taking advantage of it.”

The first biologically disconcerting results were published last year in the journal Nature Geoscience. They came from several expeditions to an area of the deep sea between Hawaii and Mexico, where Professor Sweetman and his colleagues sent sensors to the seafloor, about 5 km deep.

This area is part of a large swath of seafloor covered in natural metal nodules, which form when dissolved metals in seawater accumulate on shell fragments or other debris. It’s a process that takes millions of years.

Sensors the team deployed repeatedly showed an increase in oxygen levels.

“I just ignored it,” Professor Sweetman told BBC News at the time, “because I had been taught that oxygen could only be obtained through photosynthesis.

Eventually, he and his colleagues stopped ignoring their readings and instead sought to understand what was going on. Experiments in their laboratory – with nodules that the team collected immersed in beakers of seawater – led the scientists to conclude that the metal pieces produced oxygen from seawater. nodules, they discovered, generated electrical currents capable of splitting (or electrolyzing) seawater molecules into hydrogen and oxygen.

Then came the backlash, in the form of rebuttals – posted online – from scientists and seabed mining companies.

One of the critics, Michael Clarke of Metals Company, a Canadian deep-sea mining company, told BBC News that the criticism focused on a “lack of scientific rigor in experimental design and data collection.” Basically, he and other critics claimed there was no oxygen production — just bubbles produced by the equipment when taking samples.

“We have ruled out that possibility,” replied Professor Sweetman. “But these [new] experiments will provide proof of this. »

This may seem like a niche technical argument, but several multi-billion dollar mining companies are already exploring the possibility of harvesting tons of these metals from the seabed.

The natural deposits they target contain metals essential to making batteries, and demand for these metals is growing rapidly as many economies shift away from fossil fuels in favor of, say, electric vehicles.

The race to extract these resources has sparked concern among environmental groups and researchers. More than 900 marine scientists from 44 countries have signed a petition highlighting environmental risks and calling for a pause in mining activity.

Speaking about his team’s latest research mission at a press conference on Friday, Professor Sweetman said: “Before we do anything, we need – as best as possible – to understand the [deep sea] ecosystem.

“I think the right decision is to wait before deciding whether this is the right thing to do as a global society.”